Dear Ray Durgnat,

Thanks for showing that criticism is an art, an area you would call ‘matters arising’. You said of your critical thinking that it is close to the school of Positif, to me it bursts with ideas like no other critic I have ever read. Your incredible fifty year career started aged 19 with an article on melodrama for Sight and Sound in 1951, a magazine you would later despise for its way of writing about films as if they themselves were literature. I can’t define you to school of critical thinking Ray, you’re just too unique. The first article I read of yours that brought this to light was your piece on O Lucky Man! (Anderson, 1973) for Film Comment in 1973, it is the most poetic film review I have ever read. http://www.filmcomment.com/article/o-lucky-man-or-the-adventures-of-a-clockwork-cheese/

‘Fifteen (or so) uneasy pieces:—The school for salesmen.—Not the deserted village but the redundant factory.—Strange denizens of a middle-class home away from home.—Explosive events among our not-so-civil service.—Medicine à la Mammon, or Human Factory Farming.—Harvest Home, or an English Il Miracolo.—How high the finance.—Flags pass, but trade remains.—Black Power considered as double-entry bookkeeping.—Another visit from the police.—From gold bars to prison bars.—Stone walls do not a prison make, if the spirit soars on wings of high ideals.—The Birdman of Wormwood Scrubs.—With the Sliver Lady Among the Savage Dossers.—Disheartening ingratitude of the lumpen.—Film director as “enlightened” Head Master.

It’s either If… or oh unlucky Jim.

Say cheese or the Clockwork Man.

Next time you say Revolution, Smile.

North by Northeast, or Opportunity Knocks, or This Is Your Life That Was. The loneliness of the long-distance commercial traveler. Did you hear the one about the death of a salesman?’ (Durgnat, Film Comment, 1973)

Your writing is very concerned with class hierarchies, you use the word ‘bourgeois’ a lot. Hence you wrote an 8,000 word review of The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (Bunuel, 1972). You believe in cognitive psychology over semiotics, film theory had its limits for you, you refer to it ‘as ‘though control’ ‘another Marxist trap’ which I agree with. http://raymonddurgnat.com/publications_full_article_the_discreet_charm_of_the_bourgeoisie.htm

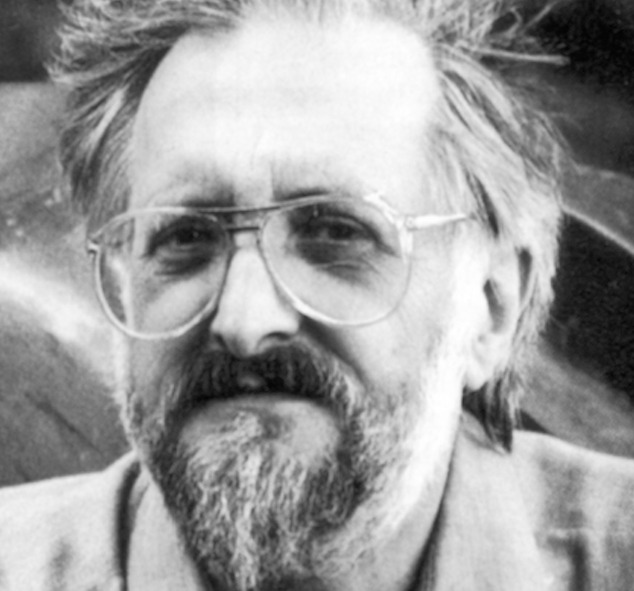

A Cambridge graduate in English Literature, you did two years of National Service for the Education Corp in Hong Kong. On your return to England you worked as a staff writer for British Associated Pictures which you described as ‘Last Year at Marienbad (Resnais, 1961) without the luxury’. In the sixties you attended Slade School of Fine Art at University College London where your Master’s thesis was a foundation on many of your future writing. Across the 1970s and briefly in 1980s who are were overseas in Canada and the US, writing, teaching, thinking. Your fifty year career has included sixteen books and many students, whom I read, remember you fondly.

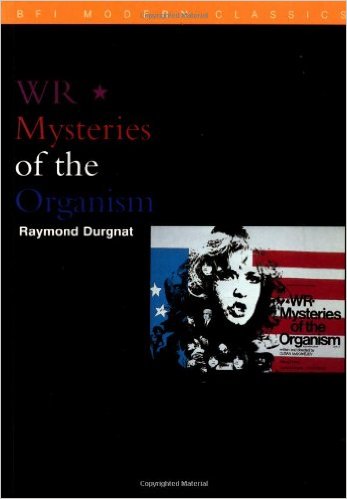

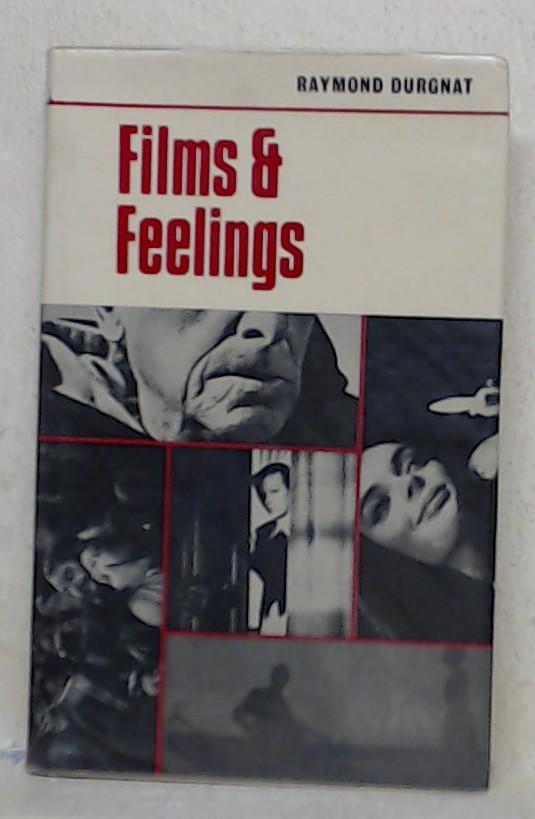

I first heard about you through Jonathan Rosenbaum who said of your most famous book Films and Feelings (1967) ‘This first collection by the most thoughtful, penetrating, and far-reaching of UK film critics ever remains scandalously overlooked and undervalued. Conceivably more ideas per page can be found here than in the work of any other English-language critic’. Adrian Martin notes that you predicated the way films are now viewed on laptops in 2016 as early in 1968! Geoff Andrew said that reading your essay on Psycho, Inside Norman Bates (1967) is the closest experience he’s had to actually watching and wondering about film as he reads it. And my favourite Kent Jones ‘Durgnat’s BFI Modern Classics book on WR [Mysteries of the Organism] was the main event of the year for me. Durgnat uses ideas the way Manny [Farber] used adjectives. He opens up every horizon around and beyond this film, and by the time I got to the end of the book, I felt like I was experiencing one of those rare days after a storm, when the wind has swept the sky clean and the clouds are racing.’ I wonder how you would react to this praise Ray, I wonder what your review of High-Rise would have said if Nic Roeg had directed it in the 70s let alone your thoughts on Bad Timing and Eyes Wide Shut, The Life of Tree etc. Your friend Charles Barr agrees with the BFI’s summation on your final book, a monograph called A Long Hard Look at Psycho (2002) is a ‘reinvention of cinema studies’. Wow, I can’t wait to read it.

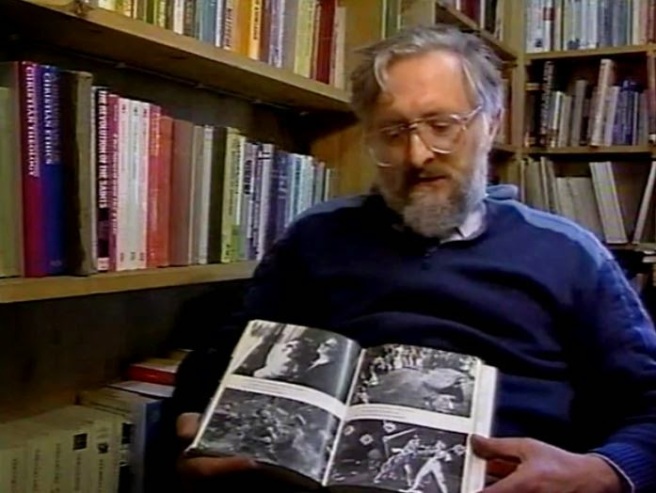

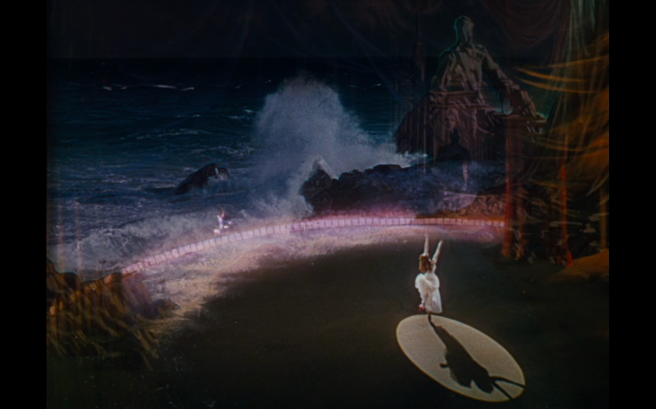

I was very moved by Jarmo Valkola’s documentary Images of the Mind: Cinematic Visions by Raymond Durgnat, your lone walks around Highbury, London and your philosophical thoughts on Michael Powell’s England, a filmmaker who you were (to my knowledge) the first critic in England to write a major critical essay championing him in Movie magazine in 1965 under the pseudonym O.O. Green as you also wrote for a rival publication Films and Filming (1954-1974) . The book on Powell that you spoke of was never sadly never finished. Having been born in Walthamstow, North East London in 1932, Powell and Pressburger’s cinema represented times that you knew well. Powell’s visuals and Pressburger’s lyrical ideas represented something else too, wonder beyond the beyond. You said that The Red Shoes (Powell and Pressburger, 1948) is the best example of illustrating the forms of cinema. https://vimeo.com/62431429

I recently found your final major essay, 10,000 words on Red Psalm (Jancso, 1972). You’re an inspiration Ray, you’ll never be bettered. I will think of you on 19th May as it is the fourteenth anniversary of your death, you were four months shy of 70. Who knows what book you might have published in 2016, maybe one on Nic Roeg, whose films you beautifully describe ‘The bloodbrother of DEVLIVERANCE is WALKABAOUT, and that of ZARDOZ is PERFORMANCE (violence meets decadence). In the films of Nicolas Roeg a self-confident civilization confronts everything which it thinks it has made alien or outgrown: the Stone Age (WALKABOUT), or pure evil (DON’T LOOK NOW), or a death-religion (PERFORMANCE), or a Houyhnhnm-like nobility (THE MAN WHO FELL TO EARTH)’.

You said something in an interview in 1977 which shocked me, you said ‘It wouldn’t break my heart if all the movies in the world were destroyed tomorrow’. You also said in 1992 on The Red Shoes, ‘Perhaps that’s the moment of the realisation of one’s liberty in relation to film, that one isn’t obeying the rules of the world. But one is borrowing from the rules of the world just what one needs and no more than one needs to create this false world. A false world but arbitrary in the best sense of being artificial of being devoted to demonstration and expression’. A critic once said of you that you had so many interests, any of them could have been your field, you chose cinema. For you cinema was a way of understanding the world. To paraphrase Mark Cousins, ‘talk about being close to the contours of the movies, a place I want to be’.

Rest in Peace,

Peter Larkin